Lucy

“Some days are fine, you can get through them and that’s fine but you do have some very bad days and you have to accept that’s part of your life, but it’s also the price that you pay for having loved them and so I’d rather have that grief than have not had the love.”

30% of children diagnosed with a rare disease die before their 5th birthday. Their families feel isolated and often their loved ones simply do not know what to do or say to support them. Sometimes all they need is to simply know someone is there for them and that they can talk about their loved one as and when they need to.

This project was designed to start the conversation about child bereavement due to rare disease and highlight the need for more support for families. Toni shared her and her family’s experience of dealing with grief due to Niemann-Pick disease.

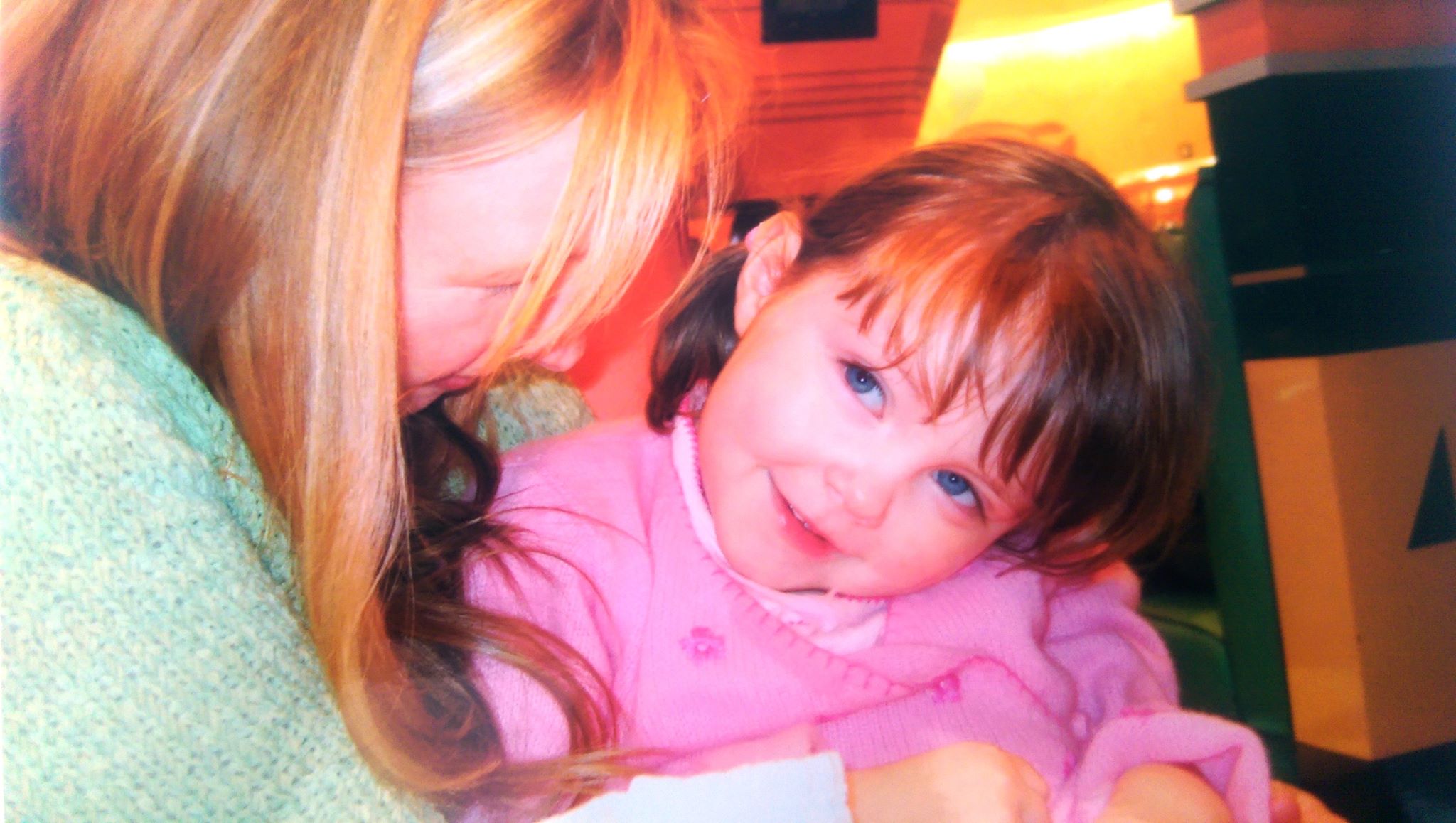

“Lucy was our daughter. She was born in September in 2003 and was much-wanted and perfect. Unfortunately she wasn’t very well when she was born; at first they said she may have Leukaemia and then various other things before, at about 5 weeks old, they said it could be Niemann-Pick disease. We started to be tested for that and then early in September 2003, it was confirmed and she had a condition called Niemann-Pick disease, Type C.

I had a very normal pregnancy with Lucy although I ended up having a caesarean section because she was breach. When she was born we were told that she seemed much, much younger and she also had a very enlarged tummy, which we subsequently found out was due to her liver and spleen being enlarged. Up until that point we didn’t know anything was wrong and in fact we were told initially that it was possibly due to wind. Lucy was in the special care baby unit for two weeks and so life had been turned upside down even before we had that initial diagnosis.

Looking back, the main person who supported us in the hospital during that time and who is still a friend today, was our midwife who was absolutely amazing. She was there for us all the way through, and still is, which is unbelievable.

When I think about some of the people we encountered during that time who were, not necessarily without compassion, they were just doing their job, but without a thought for what the person in front of them was going through. For instance, bringing 10 students round to listen in while I’m sitting there holding my child and talking about her in front of me and saying what they thought might be happening is not right. There were a lot of things that I think could change and should change when it comes to mums, especially mums who have either poorly children or have just lost a child, being on a maternity ward and being subjected to things like that.

When Lucy was discharged home, she didn’t actually have a diagnosis. We were going through lots of different tests and appointments and were told not to take her to crowded places in case she caught anything. We lived a very isolated life for the first 5 to 6 weeks.”

“The day we actually got the possible diagnosis of Niemann-Pick was the day we were going to a friend’s wedding and my husband was best man. I remember it so clearly, I had just got all dressed up and my mum was babysitting when the phone rang and it was one of the doctors, the junior doctor from the ward. He said we think we know what Lucy has, it’s called Niemann-Pick disease and she’ll be very difficult to live with. I remember saying, ‘what does that mean, tell me what that means’. He couldn’t really tell me and his definition of being ‘very difficult to live with’ was having learning difficulties and being cognitively impaired. When I think back to that call, there is so much I would like to tell him about the way he gave us this news but at the time all I could do was just be quiet and silent. It is very hard to give a response to that news when you’re talking about a very small child that’s sitting being cuddled by you, who you absolutely love and adore, and somebody says that they’re going to be very difficult to live with. I think that was one of the worst things that anyone said to us during that time.

To give such a serious diagnosis over the telephone is wrong on so many levels. Fair enough it was the correct diagnosis but I think it could have been handled a lot more sensitively. In addition to that, everyone is different and people who have disabilities can live very good lives and it doesn’t mean that they’re difficult to live with. I think that’s a very broad and unfair statement.

We went to see a consultant at a hospital in Newcastle and had a very difficult meeting. He told us that Lucy was going to have perhaps 6 months, if we were lucky, and we should take her home and make memories. He didn’t say it nicely, he said ‘she’s going to be spastic’, that was the term he used, and ‘take her home to die’. And then he said to me ‘why are you crying?’.

Stuart, my husband, was with me, along with my best friend, Lucy’s godmother. It is lucky she was there because I was in no fit state to drive home or do anything and Stuart had to go back to work. After the appointment, Melanie, Lucy’s godmother, took me for a coffee with Lucy, and we went to the hospital café. When we came out, we passed the consultant in the corridor and he said ‘oh it’s good to see you’ve stopped crying eventually’. We just stared at him in disgust and walked past.”

“I think it’s incredibly important that the consultants think about the way in which they break news. Every child’s journey is different and they really need to keep that in mind before they say things that could have a profound effect on somebody’s life.”

“Following that appointment, for probably 2 or 3 days, I didn’t even try and cope with it. I basically sat there and stared into space. My friend Melanie had been on the internet and looked up the condition - at the time we didn’t even have a computer. She came back with some sheets of paper about Niemann-Pick disease that she’d found on the internet and said, ‘I’ve found this, I don’t want to give you it though, it’s devastating’. It was awful to read and it wasn’t a good outcome at all, it was a horrible prognosis and really upsetting. But then, at the same time she found a number for what was the Niemann-Pick Disease Group UK and I rang and spoke to the founder, Susan Green, who gave me loads of hope and information and I’ll never forget that.

Hope is incredibly important, because hope gets you one from moment to the next, from one moment to the hour, from the hour to the day and the only way forward sometimes is to go one step at a time.

I think those conversations about it being a terminal disease or it being incurable and not having an effective treatment have to come from the clinician and they have to be very appropriate and come at the right time, at a time when people can actually listen. I think when somebody says to you, your child has a terminal illness and they may not have very long to live, you don’t really listen to much else after that. It took me a while to be able to take it all in and listen.

We told immediate family and we handed them a leaflet basically that the charity had given us, as it was easier that way because I couldn’t even speak the words Niemann-Pick disease, probably for about a year and a half after Lucy was diagnosed. Telling anyone else, we just said that she had a very rare disease and she probably wasn’t going to live very long, and that was all we said to people because it was too difficult to explain, and too emotional.

We were able to forget sometimes. I think for the first two years of Lucy’s life, she didn’t progress normally, she didn’t meet her milestones in the normal way but she did manage to do a lot of things. She was a very happy child and she did crawl, and she played, and she laughed. She didn’t really walk or talk but she was a very funny little girl, she was just lovely. She would cuddle Jess, and pat it, really caring and loving and an absolute delight to be with, all the time. It was only when you saw her with other children and realised the gap in her development that it brought it home to you exactly what the condition was doing, and so it probably wasn’t until she was around 2 years old that we had to face things properly because you could see the progression of the condition at that point.

I feel very grateful. Grateful that I had the opportunity to be her mother and not just grateful for the time that we had for Lucy, but everything that she taught us, the people that she brought into our lives, the different perspectives that she gave me, it’s absolutely amazing. It might have been a short time but it will last forever and of course I had the additional experiences with Lucy’s brother and sister, Hannah and Sam, which again, very grateful for and have taught us such a lot.

Meeting other people who are in a similar situation is of vast importance. It’s absolutely been one of the most important things in my life. Those initial conversations that we had with Susan Green were life-saving in many ways. They really helped us and all of the people that we’ve met so far, the community that I work with now, I would credit them all with having got us to where we are today and for me being able to sit here and actually speak and not just be an emotional puddle on the floor.

Life goes on afterwards but in a very different way and it’s never the same. Grief is always there, it doesn’t go away, it’s always there. Some days are fine, you can get through them and that’s fine but you do have some very bad days and you have to accept that’s part of your life, but it’s also the price that you pay for having loved them and so I’d rather have that grief than have not had the love.

After Lucy died, it didn’t feel right that the sun still rose or that BBC news was on at 6 o’clock, silly things, I used to get so upset that life hadn’t stopped, the clocks hadn’t stopped because my daughter isn’t here anymore and why wasn’t anyone taking any notice, but that’s life and grief isn’t it and it affects everyone at different times. Life goes on whether you like it or not so it’s how you cope and deal with it afterwards that really matters.”

Hear the other Stories

What is Niemann-Pick disease?

Niemann-Pick diseases are a group of rare inherited lysosomal storage disorders that can affect both children and adults.

Acid Sphingomyelinase Deficiency (ASMD) includes Niemann-Pick Disease Type A (NP-A) and Type B (NP-B), which are caused by a lack of the enzyme acid sphingomyelinase leading to a build-up of toxic materials in the body.

Niemann-Pick Disease Type C (NP-C) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease caused by an accumulation of lipids (fats) in the liver, brain and spleen.

For more information or support, visit www.npuk.org.

If you wish to discuss this project or reproduce any images or story, please contact ceri@samebutdifferentcic.org.uk. The photographer on this project is Ceridwen Hughes (www.ceridwenhughes.com)