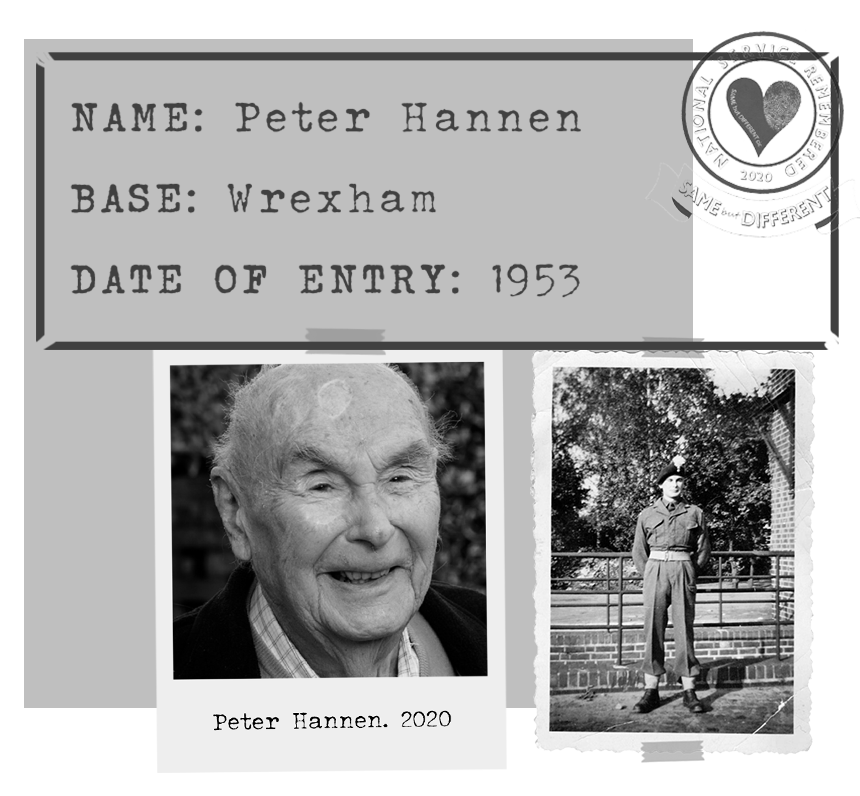

“When you first went in, it was strict. It had to be because everyone had to be brought down to this one level if you like - it had to be.”

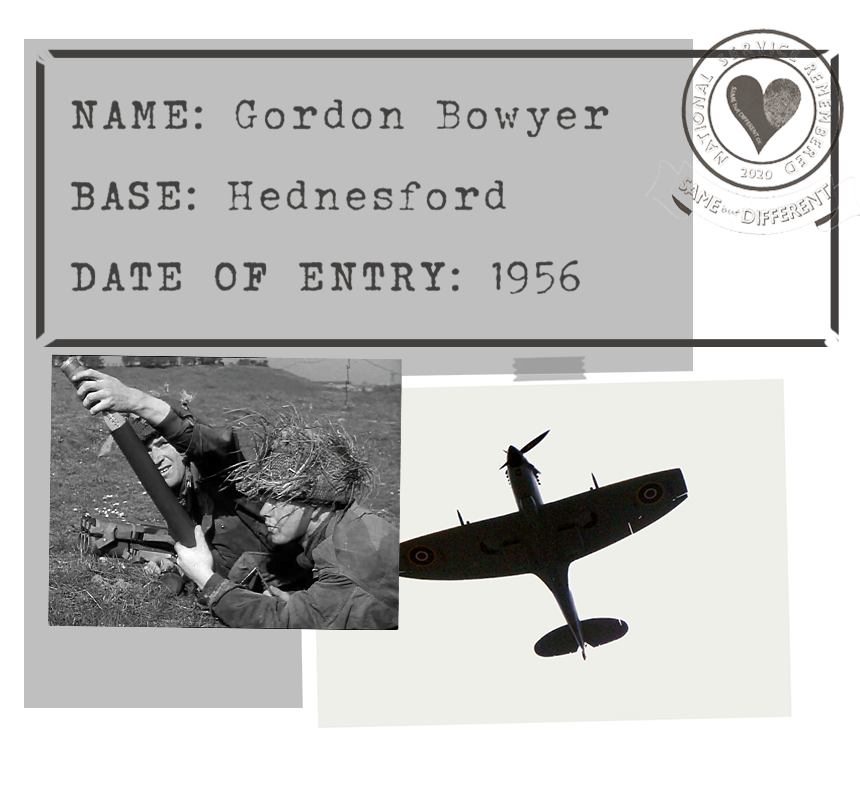

It was 1956 when I joined the National Service, I was 21.

It wasn’t the normal way of joining – I applied to go as an air crew. I went down to RAF Hornchurch in Essex for the air crew selection, and spent four days there. There were two days of medical and physical examinations, then two days of aptitude testing. There were about 30 of us on that intake. After the selection, you’d be offered either pilot training or some other occupation training.

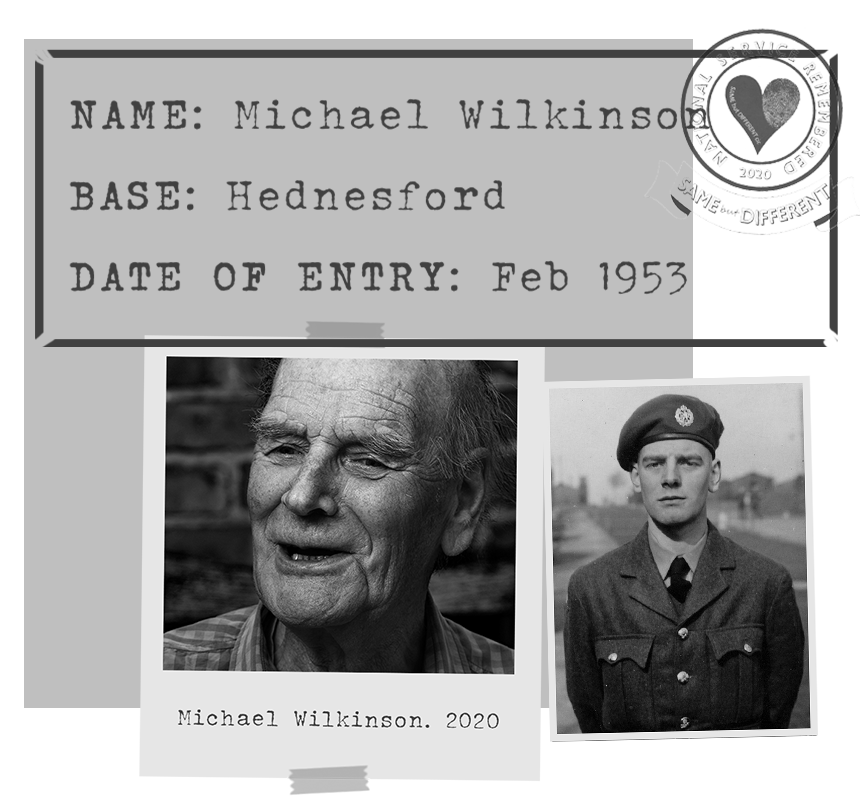

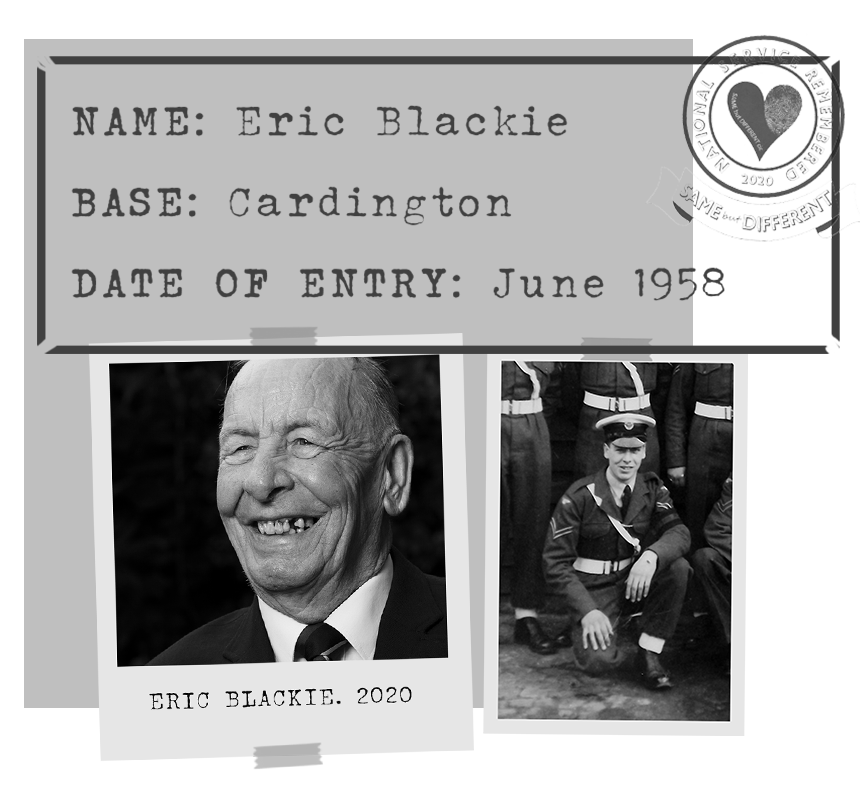

I was offered an air gunners training but I thought ‘no, I’m not going to sign on for 12 years to be an Air Gunner’. So I went to RAF Cardington for my National Service training. At RAF Cardington we were given our RAF kit, and then I was sent to RAF Hednesford where I did my eight weeks basic training, which was called square-bashing, which was just marching around the square.

RAF Hednesford is quite high up in Staffordshire, indeed Hednesford is actually on top of Cannock Chase so it was very exposed. And indeed, it was winter, and there was a lot of snow so it was cold, very cold. We lived in standard wooden billets with two stoves in the middle. They were coke stoves, and it was one of the duties to go around and fill up the stoves with coke. But you had to be so careful - once, a young chap I knew vaguely from school, was on coke duty, and as he was filling the coke up, he spilt it on the floor and the Corporal went ballistic because the floors of the billet were absolutely spotless. You know they were just ordinary brown lino but they were glistening because you had to get down on your hands and knees and polish them every day, that was part of the discipline. When he spilt it, he scratched the floor and the Corporal made him scrub and polish that area on his hands and knees in front of everybody.

“Once, a young chap I knew vaguely from school, was on coke duty, and as he was filling the coke up, he spilt it on the floor and the Corporal went ballistic because the floors of the billet were absolutely spotless. ”

After the eight weeks training at Hednesford, we were allocated a trade. I chose to do radio training which covers radar and radio, which was at RAF Locking, near Weston-Super-Mare. The initial training at RAF Locking was more or less like going to school because there was very little square-bashing, it was basically sitting down and training and learning. The worst thing about RAF Locking was that every morning the whole camp was woken by the sound of bagpipes. Beside National Service, the RAF also had what they call apprentices, young people who had signed on for 12 years, of which they did 3 years of training. The apprentices were woken up every morning at six o’clock by the sound of ‘Scotland the Brave’ being played on the bagpipes, but of course this meant that the whole camp was woken by the sound of bagpipes!

After training you got selected for either Air Crew Radar, where you were working on airplanes, or ground radar and then you got posted and your posting could be anywhere.

I was posted to RAF Borgentreich, so I was sent down to Harwich where I got on a ship which sailed over to the hook of Holland.

When I arrived, there were four trains: red, blue, yellow and green trains which were all going to different destinations in Europe. RAF Borgentreich was brand new so the accommodation was very good. It wasn’t a big camp, there was only about 200 people there, because all we were looking after was radar sites.

There were no windows on the cabin that we worked in, because it was rotating. The actual building itself was a fixed building, just the cabin used to rotate, but once you were inside, it was fine because, although it was turning, there was no point of reference to see anything so you didn’t feel the spin. All the equipment was housed in the building. You could get out though and go down to the bunker to watch the radar. We used to go down sometimes and watch the Germans, the East Germans or the Russians coming up to the border, we could pick them out on the radar. Our guys were plotting them; RAF Borgentreich was a controlled station so if there was a threat, they had the control to put fighters up.

We worked in 12 hour shifts. If you were on the day shift, you would be taken to site at seven o’clock in the morning. During the day we were always busy servicing the radar but you didn’t do any servicing at night. Of course you had to be there at night in case there was a fire, or in case part of the electrical equipment failed, but generally our Sargent didn’t mind if we slept as long as one of us stayed awake, so we used to take it in turns to sleep. Another good thing about this was that we didn’t get as many kit inspections, because we were working shifts. If the Officer was coming round, we’d say ‘sorry Sir, we’ve got people asleep after being on the night shift’. You wouldn’t get away with it all of the time though. Our Sargent was brilliant, he was a great Sargent. Unfortunately, he caught Polio and died. He went on leave to Ostend and it was the time of course when there were no Polio vaccinations and he went swimming, got Polio and died. We all went to his funeral.

We were supposed to be there for 12 months.

But a group of us were discharged early to be Auxiliary firefighters, so we were sent back to the UK to do a full firefighting training course at Moreton in Marsh, which is still a firefighting college. We did two weeks there and then we were assigned to run Green Goddess Fire Engines in a state of emergency. At that time, they thought we were going to have a war with Russia, so we were being looked at as the back up to the fire service, an auxiliary fire service. Instead of the normal reserves afterwards, had we been needed, we would have been called back into the firefighting service rather than back into the RAF.

“The worst thing about RAF Locking was that every morning the whole camp was woken by the sound of bagpipes.”

I left after the two years.

If I’d have been offered a Navigator’s job, I probably would have signed on. I think we would have had to sign on for a minimum of 6 years then. I went into the RAF because of my cousin. He was in the Second World War as an air gunner and he flew a hundred missions. One hundred missions! An average life for an air gunner was about 15-20 missions max and he flew a hundred. He actually flew for a time with the famous Dam-Busters squadron as well. He was awarded a DSO and a DSC , and it was really unusual for an air gunner to get both medals, they got one but very rarely got both. He also flew, at the end of the war, with the Pathfinders. The Pathfinders were the ones who went in first to lay the targets, they put the flares down. He was always very proud of that.

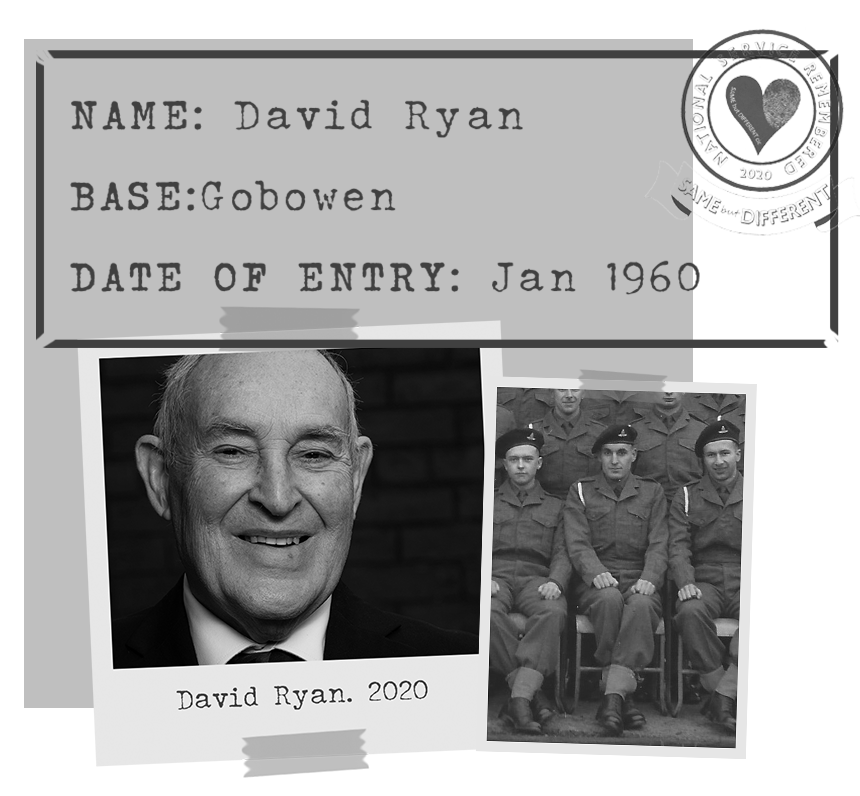

Initially, when you go in, you’re missing your friends at home but once you get to know the others, they’re all in the same boat. You’ve got to make the best of it, so you took it as it was and I think it gave me confidence. I think we all grew up, because when you first went in, it was strict. It had to be because everybody had to be brought down to this one level, if you like. I remember many years later when I was out, one afternoon this man came up to me who had remembered me from RAF Hednesford. He was one of our Corporals there and he said to me “we had to be strict you know, it wasn’t personal.” I think the discipline element was necessary, and it was certainly necessary for some of the men who had never had a lot of discipline, and they were the ones who often found it more difficult.

There was people from all over the country, and we had some guys from pretty rough backgrounds.

One guy in our billet was bragging that he’d knifed his father. The Corporal challenged him to a round in the boxing gym, Queensbury Rules. Little did he know of course that the Corporal was a boxing champion. He was on the floor in about thirty seconds flat. Didn’t brag again. One of the drivers got sent to the glasshouse for killing geese, he used to try to hit them in the truck. The glasshouse was a military prison, which is not like a normal prison, they were up at five o’clock in the morning and then they used to have to run around the square in full kit.

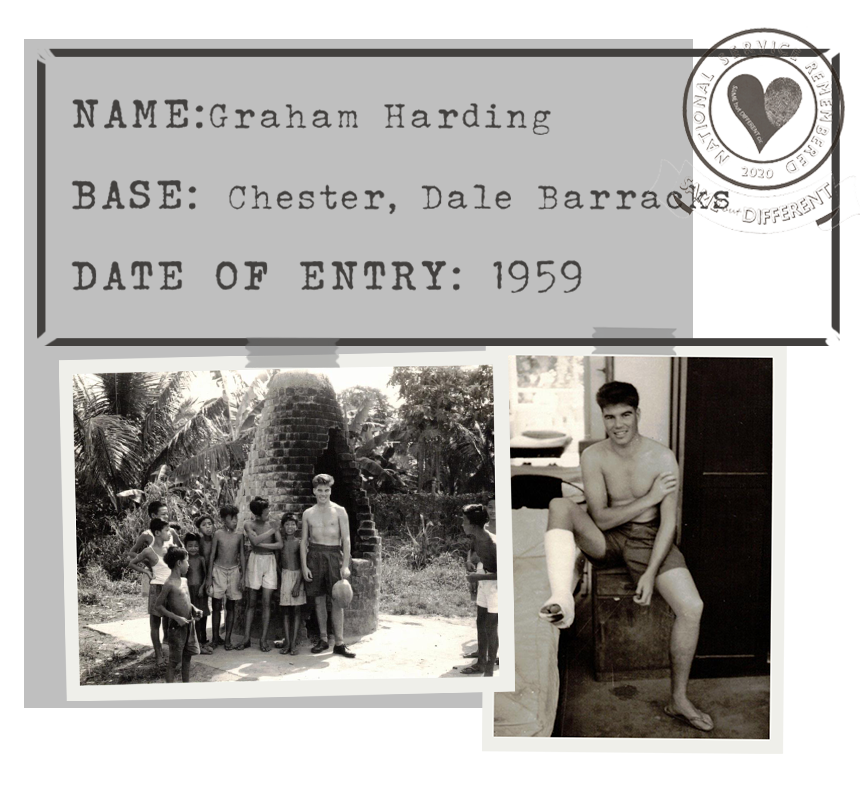

You had to go. I think National Service was an excellent thing actually because it helped a lot of young people, it motivated them to do something. I’ve always said that some of these youngsters who seem to have a lot of problems these days would benefit from that sort of discipline. You couldn’t bend the rule because the rule was the rule, and when you had a Corporal standing that close to your face shouting at you, you know, you started to take a bit of notice. For me, travel was the best part because people didn’t do a lot of travelling then. And it gave me a different perspective on life.