In 1956, my National Service date was repeatedly deferred.

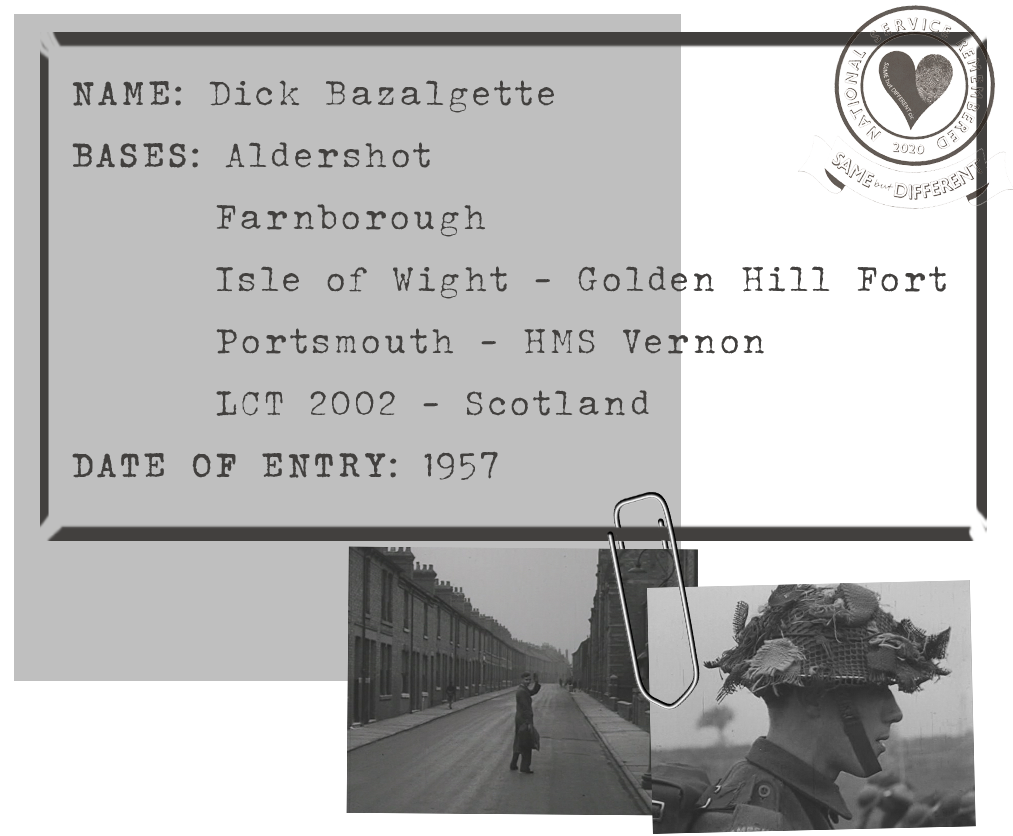

The Suez Canal fiasco had ended so I decided to ‘sign up’ as a Regular. I signed up in the Royal Army Service Corps to become a Marine Engineer. A week before starting my basic training in Aldershot, I fell off a bike and gashed my leg. When I arrived, I remember the long line of Victorian, three-story blocks of barrack rooms, interspersed with large asphalt-covered parade grounds. There were 16 beds, each with their own bedside locker and metal hanging wardrobe.

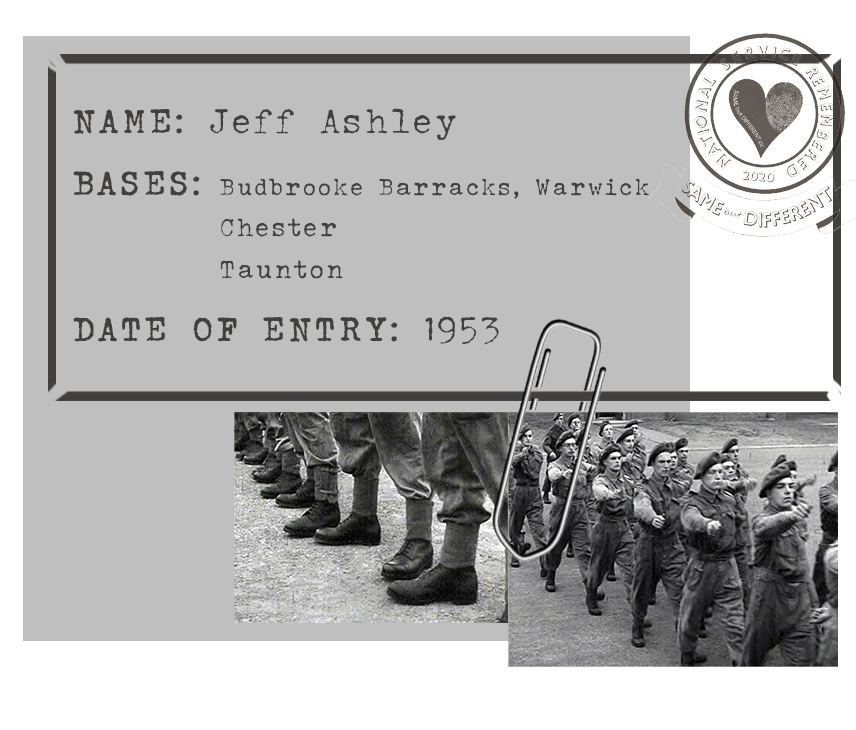

The stitches and bandages on my knee, got me out of ‘square bashing’. Instead, I was given lots of other menial tasks in the barrack room; ‘bumping’ the floor, cleaning the washroom and latrines, beds and bedding, backpacks and ammunition pouches. All were well blancoed & brasses gleaming. Everything had to be perfectly in line. On one occasion I hadn’t seen a clothes hanger on the curtain rail. I got a ‘right rollicking’ from the Section Sergeant for letting the Squad down.

The ‘Passing Out Parade’ was two weeks after I joined up. My marching and parade procedures were fairly good, and my boots were so shiny that the Inspecting Officer complimented me on the ‘mirrored’ toecaps! Actually, the polish was so thick, it flaked off very soon after the parade.

“I remember the long line of Victorian, three-story blocks of barrack rooms, interspersed with large asphalt-covered parade grounds. There were 16 beds, each with their own bedside locker and metal hanging wardrobe. ”

We were then transferred to Farnborough, where jet aero engines were being tested. We had to have our ‘jabs’, which made our right arm so stiff (always sadistically put it in the right arm) that saluting properly, with the elbow level with the shoulder, was impossible. All very amusing, being told off for an improper salute, with your elbow by your hip and your head coming down to meet your hand! We were marched everywhere and went out on regular cross country route marches. We visited the ranges, firing rifles, sten guns and bren guns. At the end of the day, we were all deaf, with ringing in the ears, not only from firing the guns but also from the bullets whizzing over head when in the butts. There were no ear protectors or earplugs. We also had to do regular Guard Duty in full kit. This included our ammunition pouches and back packs (stuffed with newspaper to 'keep their shape’). We were given a pickaxe handle to ward off the IRA who, it was feared, would come to 'empty' the Armoury, which we were expected to protect with our lives. One of the other areas we 'guarded', was a fuel dump near Fleet. 6 squaddies and an NCO, 2 at a time strolled around the perimeter wire fence, in 2-hour shifts, often smoking by the fuel tanks! The best part was the fresh eggs and bacon cooked, by ourselves, in the Guard hut!

The ‘engineering training’ was by NCOs who read out of the notebooks that they had written when they were squaddies.

One particular Sergeant, told us that sulphuric acid was SO3 and when it was diluted, was H2SO4. Even when I showed him my old chemistry book, he would not be convinced. That was what he was taught, so it must be right. We then moved to the Isle of Wight, to Golden Hill Fort. It is a circular brick building, one room wide with two stories, surrounded by rooftop high earthworks to disguise it. In the centre, was a parking area/parade ground, entered by a tunnel/archway with the guardroom on one side.

The only really memorable and shocking event was when an SAR helicopter brought ashore a body which had been in the water a week. Deposited what was left of it, on the end of the jetty, white polo neck jersey and black trousers. Horrific! Smell and sight!

“We had to have our ‘jabs’, which made our right arm so stiff (always sadistically put it in the right arm) that saluting properly, with the elbow level with the shoulder, was impossible.”

After passing out of initial training, I was posted to Portsmouth, HMS Vernon.

The LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) when in Portsmouth, were moored on buoys, in the centre of the harbour. My accommodation was in Southsea Castle, an Army barracks at that time, in an uninsulated wooden hut, with cracks in and between the planks which you could literally see through! The wind ‘didn’t half whistle through them’! We slept with our greatcoats and duffle coats over the blankets.

One day, it was blowing a gale and sleeting; the snow and sleet was horizontal. Major Cuff, our Company CO, was bringing in the 'Flagship', to be moored. I was 'deposited' on the mooring buoy, dressed in battle dress, duffle coat and Wellington boots. We didn't wear lifebelts in those days! The coxswain took the launch off about twenty yards away. Because of the strength of the wind, the LCT came in downwind, instead of into the wind. It must have still been doing at least eight knots. The Number one and mooring crew were gesturing madly to the bridge to slow down with looks of horror. My buoy was hit smack on the bow. I linked my arms through the big ring and held on for dear life, expecting to be dragged under. Fortunately, the buoy stayed afloat and we rolled quite fast down the side like a whirligig at the fair! The launch was fast to get my aid thank goodness. I don't think I would have survived long in those clothes and boots, if I had fallen in! I did manage to get the mooring ropes attached to the ring, but Major Cuff never checked how I was! When I got home and told everybody, my father pointed out that I should not use my CO's name backwards, in front of my mother!

Between 7.30pm and 10.30pm, we were free to do whatever we wanted, except drink!

Most nights I went to the NAAFI Club in town and enjoyed Scottish Dancing. Even though I wasn't an officer, I managed to play squash at the Officer's Club. Through my contacts there, I was invited to play rugby for United Services. The Scottish scrum half, Tremain Rudd, was in the team.

I was posted to join ‘LCT 2002’ in Scotland. Armed with travel warrants, I took the overnight train to Stranraer. The LCT was moored halfway down the Loch Ryan, at Cairn Ryan. The smell of old, heavy oil and the lack of ventilation was the first to strike me, followed by the constant ‘thummbling’ (a mix of thumping, rumbling & humming!) vibration from the generators.

Day to day life onboard was routine and mundane. We lived in brown dungarees or old jeans. They got very oily! The regular run was out to St. Kilda, the most westward Hebridean Island. There was a radar station on the top of the peak, manned by the RAF. When at sea, we did 4 hours ‘on duty’ and 8 hours off, two of us at a time. Conversing in the engine room, with all four engines running was virtually impossible. We literally shouted, with our mouths right by the other’s ear. Then it took a few seconds for the brain to decipher the sounds of words from that of the engines.

“I was ‘deposited’ on the mooring buoy, dressed in battle dress, duffle coat and Wellington boots. We didn’t wear lifebelts in those days! ”

It was a glorious summer.

The temperature got up to 90 degrees F. Too hot for shirts and trousers, so we were all in shorts. Many of the deck crew were on the foredeck, chipping paint and working on the mooring winches. I was working in a small, tight, confined control compartment under the foredeck. It was mid-morning and there was a sudden, loud bang. It was like I was inside a great drum making my ears ring. I rushed angrily out to swear at them. They were all staring and pointing toward the stern. There, fluttering down, were shirts and other garments which had been on the stern deck washing line. Smoke was hanging in the air. We all rushed to find out what had happened. We got there just as the wee Glaswegian engineer climbed out of the stern compartment, saying, “I shouldn’t have done that”. His hair was all frizzled and his skin all burnt. We laid him down, covered him with a blanket as he was shivering. An ambulance was called which came very quickly. Poor lad had 90% burns. He only lived for another 12 hours. He had been washing down the steering gear, using an open bucket of petrol. A pint of evaporated petrol was equivalent to a pound of dynamite! Because he was on CB (confined to boat) for some misdemeanour, he had been given this task to be done in the evening. It is assumed that he opened the door of the drip feed boiler, to throw in the petrol laden cotton waste he had used. The explosion was heard four miles away and thought to have been a land mine going off.

Someone said that another lad was down there. A breathing mask with a long hose was fetched and I volunteered to go down in search of him. The ladder was partly detached from the bulkhead and I couldn’t see my hand in front of my face. The deck plates had all been lifted and scattered, so I had to feel my way, climbing over the drive shafts, rudder hydraulics and the 18” high metal support beam. I hadn’t been down there long before I was called back as the chap had gone to the tool store. To clear the smoke and fumes, I went down again with an electric fan. The navigation WO told me that I should have put more clothes on before going down because it was common for there to have been a secondary explosion. I was still only in shorts and the electric fan could have sparked! It was lucky I didn’t know!

One weekend at home, I was asked to play for the Quins Wanderers 2nd team as the fullback had not arrived.

I was kitted out with everything, including jockstrap! Quarter of an hour into the game a chap landed on me with both knees into my ribs. I was ‘winded’ and it really hurt but I played the whole game despite the pain in my side. Two weeks later, when this pain in my side was not getting any better, I reported to the MO in HMS Victory. Following an x-ray, I went back on board. Later that morning, we were signalled, “Was there a Bazalgette onboard? Put him on a stretcher and don’t let him move”. I had been carrying cylinder heads up and down the vertical ladder, on my shoulder. It appeared I had four ribs broken. A boat came to take me to the dock, then transferred into an ambulance, taken all the way round Portsmouth Harbour to Hasler Hospital which was less than a quarter of a mile from the boat! After shaving then strapping my chest, I was put to bed. I was in there for a week before going home for four weeks. When the orderly removed the strapping which had my hair growing through it, he really enjoyed it! No compassion!