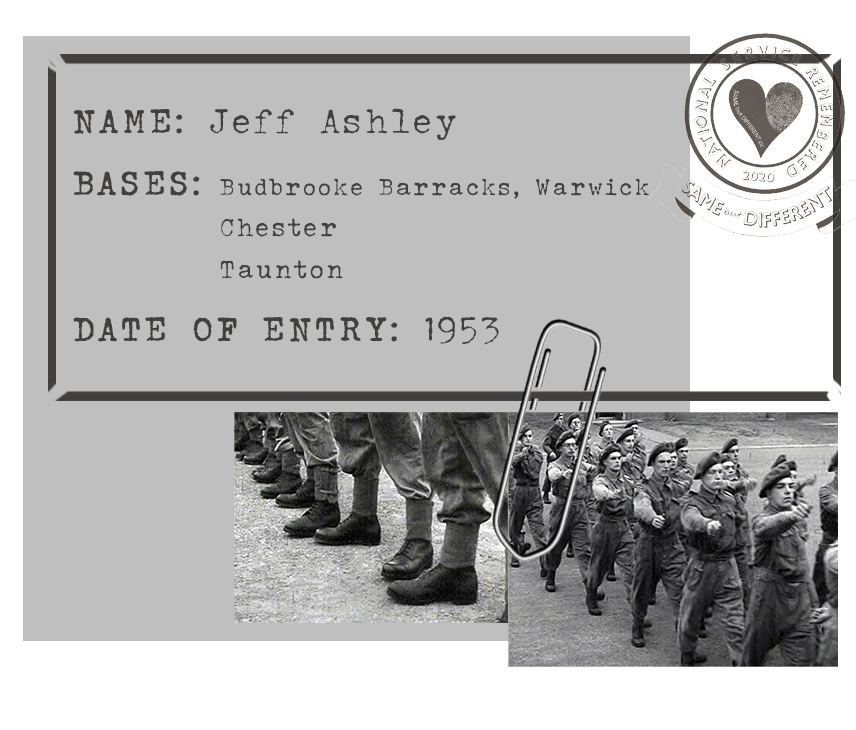

I was 18 when I was conscripted into the army on 23rd July 1953, for 2 years.

I reported to Budbrooke Barracks, in Warwick, the HQ of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. I lived in the coal mining village of Baddesley Ensor, on the advice of my father, a pitman, decided not to go down the local coal mine as many of my fellow pupils had done when leaving school at 15. Coal mining was a reserved occupation and if young men decided to stay in the mines until they were 26, they were not subject to being called up.

I entered the army with some trepidation, as an innocent country lad with no experience of the wider world but practically all my new companions had also been snatched from their mother’s aprons strings. After being kitted out we were placed in the merciless hands of drill NCO’s. I quickly adapted to the discipline and training but the army had a problem with me, I was as fit as a fiddle but 6’ tall and only 9 stone, 3oz, a veritable lath. When standing to attention I wasn’t distinguishable from my .303 Lee Enfield rifle so deemed not suitable for Infantry.

I was sent away to a special camp in Chester to fatten me up, with a lot more conscripts in the same stick-like physical state; we were fed very good high protein food and did work outs in the gym most of the day. We were weighed every week and I put on 2 pounds, but by the end of a month had lost it all, but I was as fit as a butcher’s dog.

Discipline was strict and the training staff, non-commissioned officers , NCOs, corporals to sergeant majors kept us busy every minute of waking hours, shouted at, made to do menial tasks, painting stones white, cutting grass with scissors, but importantly concentrate on our kit, making our boots that shiny you could see your face in the toe caps, blanco our belts and gaiters daily, polish brass buttons, but the most traumatic time was the kit inspection, held once a week during basic training.

“I entered the army with some trepidation, as an innocent country lad with no experience of the wider world but practically all my new companions had also been snatched from their mother’s aprons strings. ”

We lived inn Nissan huts, sheds with semi-circular corrugated roofs which slept about 20 to 30 men. Each squaddie had a metal framed bed, a bedside locker and a wardrobe for our greatcoat and uniforms. There was a coal and wood stove in the middle of the room, which didn’t warm the hut at all in winter. Each morning we had to strip our bed and make the sheets and blankets into a neat bed block. Every bit of our kit was laid out on the bed in a prescribed layout, neat, tidy, clean and immaculate. The kit was inspected by an officer accompanied by the drill corporal, sergeant and sergeant major, any faulty layout was severely dealt with including a screaming expletive doubting ones parentage and if it wasn’t quite right, the bed was often tipped over and the luckless soldier made to do it again, properly; it was a difficult time for us soldiers.

Many National Servicemen tried to make life as easy as possible by doing as little as they could, very difficult under the discipline of the forces with many regular soldiers in the non commissioned ranks. The art of doing as little as possible in the armed forces was called skiving and some men managed to do it quite successfully, but many failed.

A regular tactic was to see the Medical Officer with some physical problem, bad back, poor feet, skin disease etc. but it was difficult to convince an experienced doctor, one had to have a really genuine problem, which was often not the case.

I can recall one guy who had a note from the MO saying he couldn't wear boots and he wasn’t able to do drill or take part in active soldiering; he wandered about camp with a piece of paper in his hand doing very little. When this guy was due for demobilisation, he said, “well I won’t need that any more” and put his medical note in the bin, admitting there was nothing wrong with his feet, but his was a rare case. An instance I recall was when a guy was swimming, he claims in the Rhine, and he was hit on the head by a barge. He feigned a brain injury and was hospitalised. He started saying and doing all kinds of silly things, talking gibberish, etc. As he was getting nowhere, he decided on some action. He locked himself in the toilet and refused to come out. Hearing that three men were going to charge the door down, he quietly slipped the catch and flattened himself at the side of the wall - three burly men hit basically an unfastened door and went straight to the back of the cubicle at speed and finished up in an untidy heap. Our skiver thought it was hilarious, but nobody else did. One day he overheard doctors at the end of his bed talking about carrying out some brain surgery so he decided he should slowly get better and eventually return to duty. There is I am sure many more examples of successful and unsuccessful skiving.

Some soldiers took the bait of the higher pay if they signed on as regular soldiers and I did, eventually serving 3 1/2 years instead of 2 but perhaps perversely I enjoyed my time in the army and didn’t do any skiving.

On one occasion we were taken into the countryside to an army rifle shooting range.

We were fully equipped with back packs, ammunition pouches and eating kit (we were fed from a field kitchen). Near the range I spotted a large mushroom, it was as big as a dinner plate, now being a country lad, I knew mushrooms were edible both cooked or raw, so I quickly picked the mushroom, trimmed the edges and put it into the tin, a nice nibble for later on. We had basic food provided by the army, which was considered adequate, but hardly sufficient for growing lads; in fact, a common letter to parents often went “Dear Mother, how’s brother, had your food parcel, send another”. A soldier with a tin of peaches in his locker was fortunate indeed.

The following morning was kit inspection day, the night before had been spent blancoeing webbing, cleaning boots and checking kit to make sure everything was in order. Some men laid their kit out the night before and slept at the side of their beds to ensure they were ready in time. On the morning of the inspection, we all stood to attention at the side of our beds, eyes to the front. I was well up the hut and listened to the furore as cynical comments that were made about some poor sods efforts.

Suddenly I realised the mushroom picked the previous day was still in my mess tins, Gordon Bennett! If one of the inspecting group opened my mess tins I was in serious trouble. It was no good suggesting the army feed us better, sarcasm was the privilege of the NCOs. I froze; there was nothing I could do but hope. The inspecting party reached the next bed to mine and the sergeant opened the guy’s mess tins. It was now my turn, the inspecting party all viewed my kit, probably for a few seconds, mercy be, they moved on, I’d had a lucky escape.

“A soldier with a tin of peaches in his locker was fortunate indeed. ”

Back to Budbrooke Barracks.

The Royal Warwick’s didn’t want me, I had to be redeployed in the army. As I had worked in a garage, I was transferred to the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers. I couldn’t be transferred straight away and was taken off basic training, but I had to be kept occupied. I was put in the barracks canteen for menial tasks and finished up in the Tin Room where all the food that had been baked on huge black tin sheets, had to be cleaned by scraping and scrubbing in hot water in large vats. The work was horrendous, there were no non-stick surfaces in those days and it was very hot, dirty and hard work, a place usually reserved for men on jankers, those men who were being punished for misdemeanours.

After two weeks I was transferred to the R. E. M.E basic training camp at Blandford Forum. As the next group of National Servicemen were not due to arrive for two weeks and the several weeks of basic training I had carried out didn’t count, I had to be keep busy until I could join the new intake. I was put in the camp canteen and put in the Tin Room for another fortnight of purgatory. It was no good protesting when you are in the army, you do as you are told, particularly when they are trying to mould young men into compliant soldiers. When my second consecutive fortnight of Tin Room hard horrible work was over, I joined a new intake of National Servicemen, completed my eight-week basic training, went on to a 3 month vehicle mechanics course at Taunton, which I enjoyed immensely and in January 1954 signed for 3 years as regular soldier, odd really.

I enjoyed my time in the armed forces, most of which was spent in Germany and had developed physically to 11 stone when I was 21. I was still thin but no longer looked like an upright Praying Mantis.